LEGO’s New Robot Language Is Awesome

Last night was a great first class of Robotics 101. Every year when we start this class with a fresh set of new students, we try something new. We have two goals in the class: first, to help the kids learn the basic skills necessary to be an effective team member on the First Lego League team in the fall - but more importantly, to cultivate an interest and help them discover a passion for engineering.

This winter, LEGO released a version of Scratch built entirely to operate with EV3 robots. It’s a dramatic improvement over the previous version, called Labview, which has been the main choice for First Lego League for years.

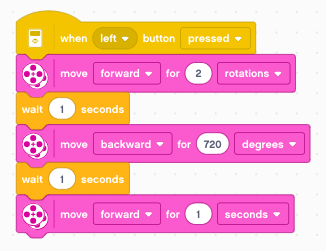

Simpler language for simpler programs

Here is the intro program showing how a robot can drive straight. In Scratch, it’s pretty clear what’s happening - the robot should move forward for 2 rotations of the wheel, then stop for a second, move backward, stop, and then forward again.

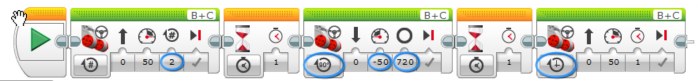

In prior years (as recently as a month ago), the official software from LEGO used LabView. This language doesn’t use language, and is laid out horizontally. The code is a bit more confusing and requires more translation for new developers as a result. Here’s the same code shown in LabView:

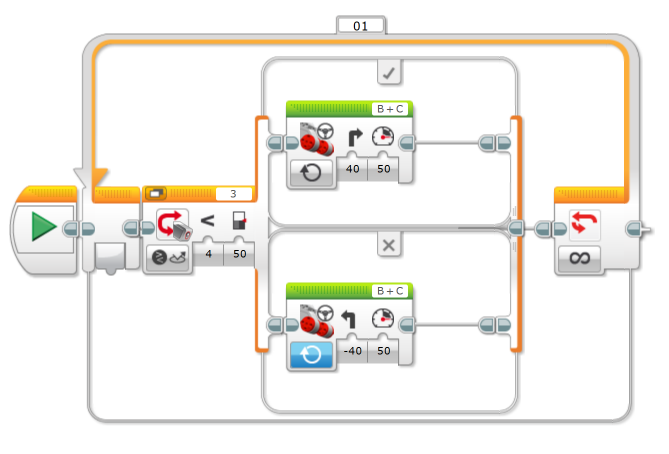

Easier to understand more complicated programs too

Labview also presents challenges as programs get more complex. It’s challenging to comment, and when programs get more than a few pieces of logic they stretch into screenfuls without great ways to organize. LEGO has a concept of a “myblock” which is kind of like a function except they can’t nest, and editing the function is a challenge.

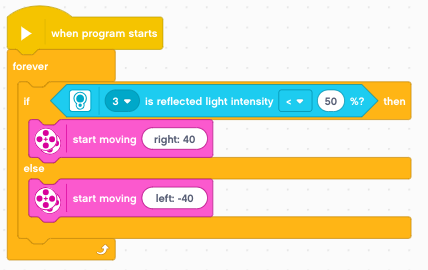

My students have often run into trouble understanding code with any switches or loops. We have to consistently re-explain what each block does (“oh, that’s a loop”) before we can get to the basic logic. For example, here’s a line follower in Labview. The robot follows the edge of a black line by using the color sensor to see whether it’s looking at a light or dark area and turning accordingly:

Even this relatively small program presents a lot of challenges. However, in Scratch the same program becomes more readable - the loop fades to the edge and the main attention is drawn to the core logic. Many of the optional features are not present unless specificaly called to. And you can sort of read the code and undresatnd roughly what it’s doing without necessarily having a lot of training in the specific blocks that are used.

Really complicated math is easier as well

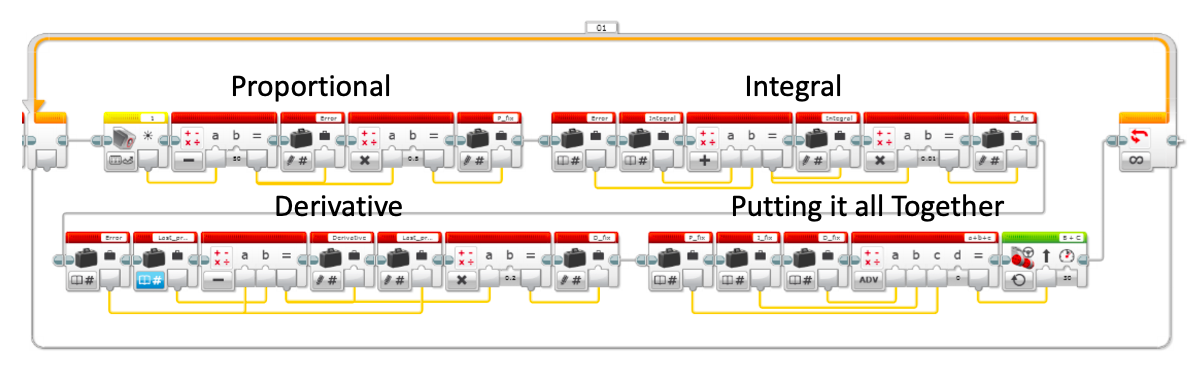

When students write in Labview, the language makes it really hard to do even basic math. Labview includes the concepts of variables and math, but values are shuttled between blocks using “data wires” which are fairly arcane and nonintuitive. As an example, an advanced form of line following is called a “PID” line follower which takes into account past behavior to more precisely follow a black line.

The EV3Lessons tutorial on PID (link) is really top-notch and walks through the different components and how they work. However, the final result is nearly unintelligible:

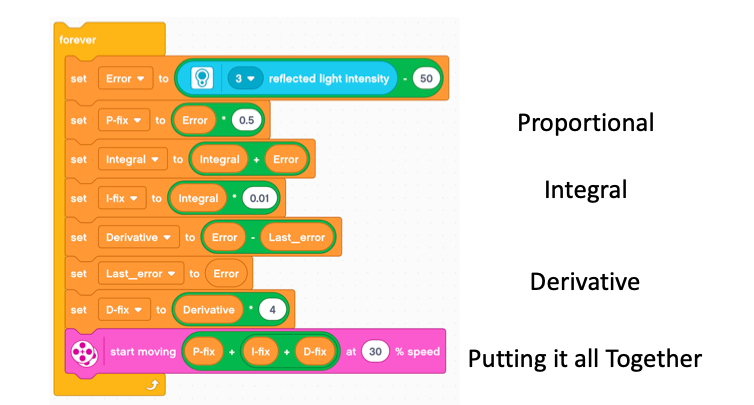

While it’s still complicated, the Scratch version at least proceeds linearly and you can trace more easily where the different values come from and how they end up determining the motor direction. This is especially true if students have experience working in any other programming language, which are more likely to use variables than data wires. Here is the code from the updated Scratch tutorial on PID (also from Ev3Lessons) - link.

I am really excited for the potential of students to learn using Scratch and build more powerful programs than what is possible with Labview.

Real world use is fully supported

Bluetooth is the primary way we encoufrage our students to connect. It has been a challenge because, well Bluetooth is finicky. But the new connection screen really helps things out. Last year, I printed out worksheets showing students all the steps to take, but this year it’s built into the program. I can tell them “Just click Connect” and they followed the prompts and all got their robots hooked up.

Here’s the connection procedure - super fast end to end.

Compared with the old software, it’s a significant improvement. And when I consider alternatives - such as MakeCode, OpenRoberta, or Python, which each involve some major lifting (either inserting a SIM card, or only connecting via USB and some magic with connected drives), it becomes obviously easier for students to just use the code out of the box.

But this new release changes it all. It’s officially supported and released by LEGO - which means we can trust that over time, it will be the mainstream standard and bugs will be fixed. It supports Bluetooth out of the box with an intuitive connection interface that’s easier tan the one in Labview.

When I tried it with the class last night, we found that the kids were able to quickly build their robots AND connect them. By the end of the one -hour class, all students had their robots built and majority had connected them to the computers and gotten them to go straight.

Teaching kids to teach themselves

One issue I ran into with MakeCode is the very limited curriculum for kids to learn. There isn’t much of an online community for EV3 Make code so I wrote all my own guides. But this is painstaking and not great - most of waht I etaech kids is how to google for their simple asnwers. There are resources like Ev3Lessons.org that are tailored to Labview and were inaccessible to my previous attempts.

But I am super grateful to the Seshan Borthers for rewriting all their lessons to support the new language as well. The website ev3lessons has been essential for my journey as a coahc the last four years and the kids have learned some great techniques; but it has hampered my other attmpets to teach b because those resources arne’t aabilable if you’ren ot using Labview. But now, they support the new language as well.

Even the Seshan brothers tools show how the new language is easier. For exampe, take this advanced lesson on how to build a proportional line follower. The Labview ersion reuires a bunch of comments in the code itself and the math operations on variables are super hard to follow - I often have to write down what the equations should be just to make any sense.

Whereas, here in the Scratch version, the essential math fits on one line and at leaste makes sense as an equation. Students can then focus on “why” the code is this way rather than on “what” it’s doing.

In addition, the built-in tutorials for Scratch are similar to those offered by the prior version of EV3, but I think the smoothness of hte language makes the enviroment a bit more slick. For example, the tutorial automatically restricts that available blocks for certain lessons so that you’ll gradually release complexity and let kids move their way up.

Also, Scratch is a mainstream coding tool that kids may have encountered in school, as well. While it’s not a major professional language (like Python), it is more standard then some of the more custom ones like Labview, Make Code or OpenRoberta, which are all robot specific. We think that will expose the kids to better, more mature tech as well.

In summary, the new Scratch language is fun and will be a better fit for our class this winter.